“Sooner or later, everyone works at the Button Shop.”

1850-1994

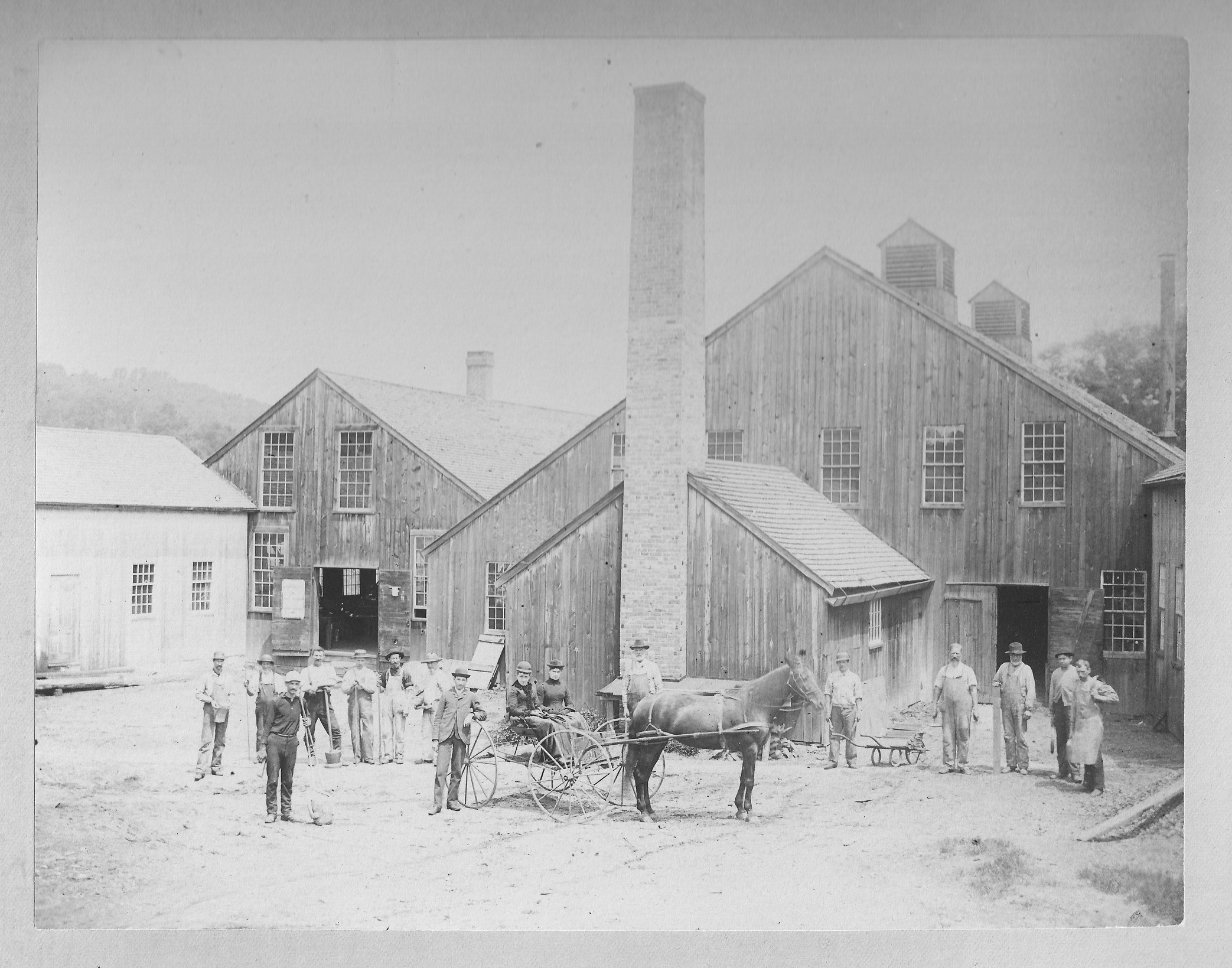

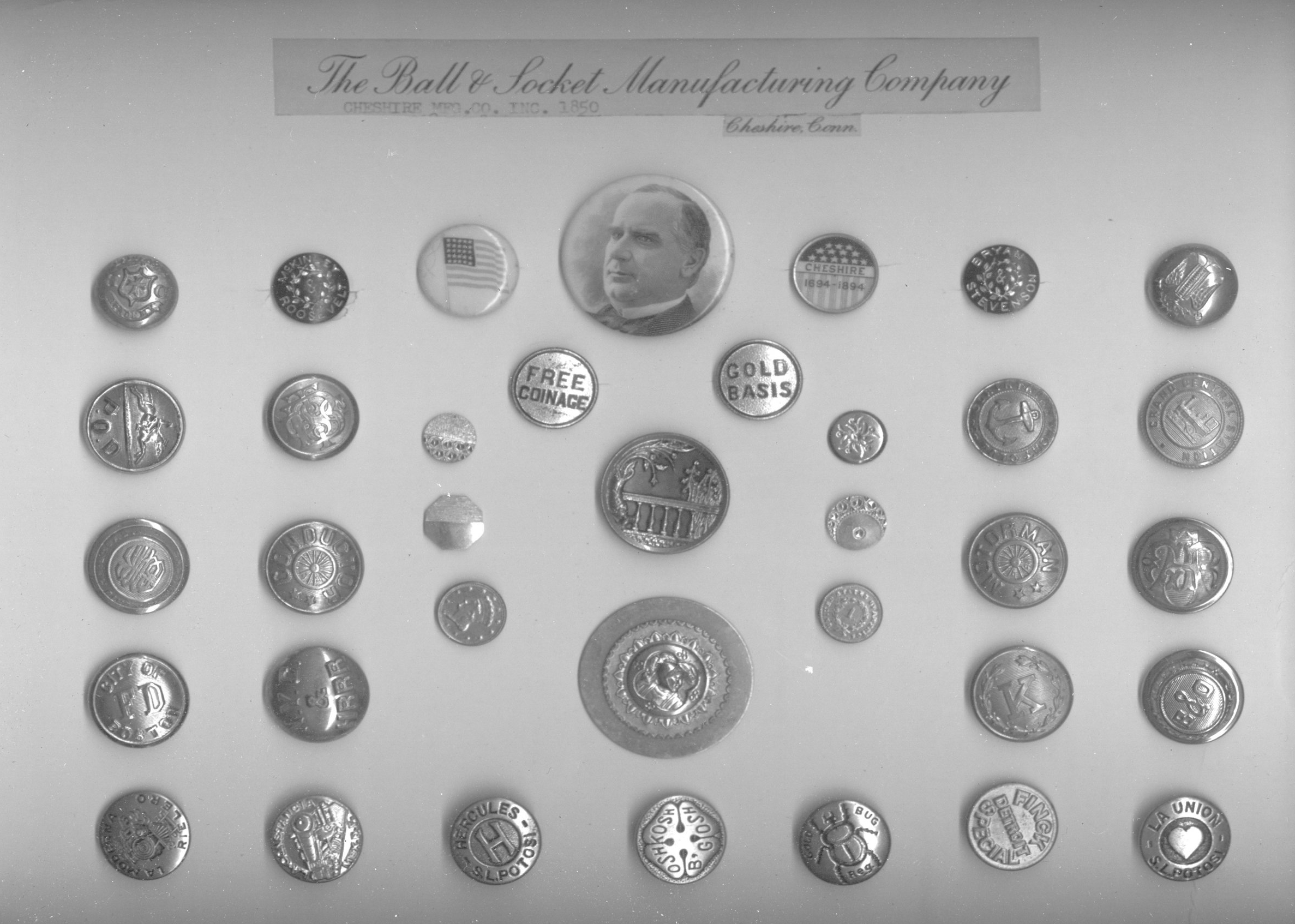

The Cheshire Manufacturing Company was incorporated on April 11, 1850, for the purpose of "the manufacture, selling and dealing in buttons of every description." In 1901, the company merged with the Ball & Socket Fastener Company of New Hampshire and became The Ball & Socket Manufacturing Company. Averaging 2.5 million gross tons per year at its peak, Ball & Socket became one of the world's largest manufacturers of metal buttons. The company even maintained a sales office and stock room at 10 West 32nd Street in the heart of New York City's garment district. For many years, it was the largest employer in Cheshire, its workforce including many women who found their first employment there. According to a local historian, there was a common saying in Cheshire that "sooner or later, everyone works at the Button Shop." After 144 years in business, changing markets brought an end to manufacturing at the site. Factory operations ceased in 1994. The property was sold to Dalton Enterprises, who owned it until Ball & Socket Arts bought it in 2014.

Legacy

The Ball & Socket Manufacturing Company's legacy resides in family histories, local lore, street names, grand homes along West Main Street and the unique architectural heritage of the buildings themselves. They tell a story of business success, civic pride and concern for the beauty of public places, from the sturdy functionality of the 1889 main factory building to the grand, 1914 neo-Jacobean front office. These handsome structures are worth preserving. A history of the site from the time of the company's centennial states, "truly, the edifice stands as a symbol. It radiates an air of permanence, speaks of a long and worthy past, and defies the future to encroach upon its dignity."

Cheshire Jewels

We may not think much about them today, but in the mid-19th century buttons were a growth market. The expanding global trade in fabrics and mass manufacture of the home sewing machine were bringing radical change to daily wear in the United States. Until then, most women had two or three dresses. Now they could have several, and older garments could be more easily updated to the latest fashion. Buttons became important trend statements, often replacing complicated hook and eye catches, ribbons, ties and temporary stitching. Though metal buttons were Ball & Socket's staple product in later years, the company made its name with fancy glass buttons known as "Cheshire Jewels," which are considered highly collectible today. Uniform buttons made by the company were worn by armed and civilian forces including U.S. forces in the Civil War, and the Free French and Soviet Armies in W.W. II. The company also made an array of other stamped metal products including jingle bells, cardholders, drawer pulls and razor parts. A "ball & socket", by the way, is what today we call a "snap" fastener—the two part thing where the ball snaps into the socket!

THE FARMINGTON CANAL: Barges, Trains and Bikes

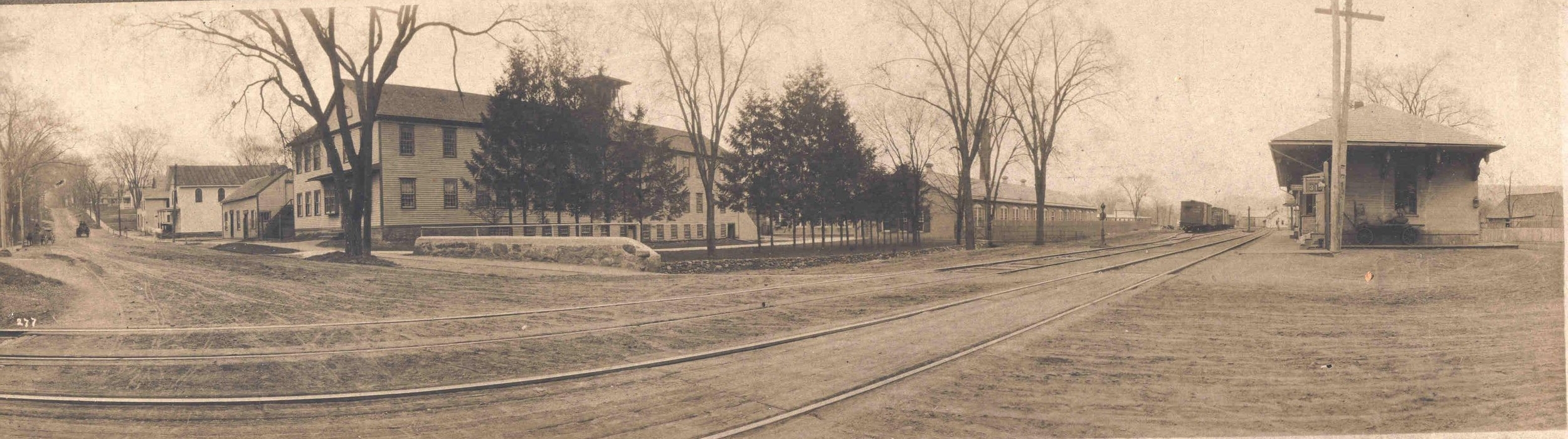

The founding directors of the Cheshire Manufacturing Company did not choose the site for their venture randomly. Two years before, in 1848, the New Haven & Northampton Railroad began service along the path of the former Farmington Canal adjacent to the site. At the time, this transportation corridor was one of the most important transportation routes in Connecticut.

The Farmington Canal, Connecticut's largest pre-railroad engineering project, grew from the rivalry between merchants in Hartford and New Haven in the push for "interior improvement" in the New England states. At issue was control of trade with the upper Connecticut River valley in Massachusetts, Vermont and New Hampshire. Hartford, on the bank of the river, was advantageously situated for this trade. By the early l820s canals had been built to bypass all the rapids on the Connecticut River except for Enfield Falls, just north of Hartford. New Haven interests hoped to take advantage of Hartford's position below the falls by building a canal over an inland route between New Haven and a point on the river in Northampton, MA.

In 1822 the 17 Connecticut towns on the route hired Benjamin Wright, engineer for the Erie Canal, to survey the proposed line. On the basis of that survey Connecticut's General Assembly chartered the Farmington Canal Co. to construct and operate the canal. Hartford representatives in the General Assembly, unable to block passage of the charter, were able, however, to prevent state subsidy of the project. Except for some assistance from New Haven, the company had to rely on private subscriptions and occasional bond sales for capitalization. In 1823 the Massachusetts legislature chartered the Hampshire and Hampden Canal Co. to build the Massachusetts section. Construction began in 1825.

The canal ran approximately 80 miles, with 58 miles in Connecticut. Over most of its length it was 4' deep, 20' wide at bottom and 36' wide at top. Towpath and embankments totaled some 30' in additional width. For most of the route the walls were simply soil banks with no shoring or capping. The 213' rise between New Haven and the Massachusetts line was taken in 28 locks. There were 3 aqueducts and some 15 culverts crossing rivers and creeks. The Connecticut section opened in 1829, the Massachusetts section in 1835; the two were merged into the New Haven and Northampton Canal Co. in 1836.

Operations were troubled from the start due to technical inadequacies and insufficient capital. The porous local soils used were not watertight; banks were frequently undercut, or simply collapsed from excess weight due to the amount of moisture absorbed. There were not enough spillways or wastegates to drain excess flow, so relatively minor rises in water level resulted in bank-destroying floods. Some locks were initially built of dry-laid sandstone blocks with timber facing. These had to be replaced with masonry laid in hydraulic cement. At the time, many of the bank cave-ins were attributed to vandalism by farmers who owned land along the canal and who were unsatisfied with reparations paid for damages to their fields caused by construction.

Traffic was substantial when the canal was navigable, even though Farmington Canal never became the predominant trade route for the upper Connecticut River valley. It was the first means of transport, besides roads, to reach much of west-central Connecticut, and canal-shipping was important to developing industries in the region. Furthermore, the traffic in freight and passengers created opportunities for private carrier services, wharf and warehouse facilities, hotels and taverns. Towns such as Plainville grew in response to canal traffic opportunities. New Haven prospered most from the canal, which began at Long Wharf and enhanced the city's position as a distribution point for New England goods bound for East Coast markets.

The plague of collapsing canal banks continued to generate repair costs exceeding revenues. The canal company had little opportunity to increase revenue in operations, since it was not empowered to operate boats, to build and lease storage facilities, or to participate in any of the ancillary functions that proved profitable to others.

In 1845 the company surveyed the route for the purpose of building a railroad. Following necessary charter revisions, the New Haven and Northampton Railroad was completed north from New Haven to Plainville in 1848, and to Simsbury in 1850. For most of their course the tracks ran on the former towpath, although in New Haven the canal bed itself became the track bed.

The problems of the Farmington Canal seem traceable to its legal origin in the General Assembly, when the Hartford interests blocked approval of state funds for construction. Capable engineering talent was available, as shown by the hiring of Benjamin Wright for the initial canal survey. But no matter how fit the designs were the company could not pay for the proper construction, so waste-water facilities were minimal and embankments were built from whatever material was immediately at hand. As the effects of these shortcuts in construction pushed maintenance costs higher, the company's resources were drained. These costs could not be recouped in operation, again because of the charter, which strictly limited the means by which the company could generate revenue. Thus the metropolitan rivalry that spawned the canal also established the pattern for its eventual failure, if conversion to a railroad can be so described, but not before the canal opened opportunities for manufacturing in inland Connecticut, and not before the canal solidified New Haven's position in the transportation networks of New England.

Portions of the canal survive today in various states of repair. The former rail bed is the site of a major rails-to-trails project that will once again connect New Haven with Northampton. For more information, visit the web site for the Farmington Canal Rail to Trail Association

[Connecticut: An Inventory of Historic Engineering and Industrial Sites; published by the Society for Industrial Archeology, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20560; 1981]